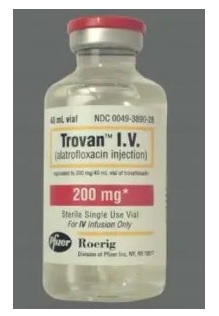

In 1996, an experimental trial took place in Nigeria. Under the cover of severe outbreaks of cholera, measles, and meningitis in northern Nigeria, Pfizer set up the secretive trials in Kano, the second largest city in Nigeria, to test its experimental antibiotic, Trovan (trovafloxacin). It tested the experimental drug on two hundred children. The children’s parents assumed that the children would receive the standard meningitis jab, but Pfizer staff instead set up two control groups. Half of the children were given the experimental Trovan, and the other hundred were given a reduced dosage of the leading meningitis equivalent. The lower dose was to help artificially skew the results in the favour of Trovan for marketing and competitive purposes.

In 2002, a group of Nigerian children and their legal guardians sued Pfizer in the US District Court for the Southern District of New York. In court documents, the plaintiffs alleged that five children who received Trovan and six children whom Pfizer had ‘low-dosed’ had died as a result, whilst others suffered paralysis, deafness and blindness. The alleged actual number of those who died due to their involvement in the trial, per Nigerian sources, is over fifty.

Pfizer was supposed to check the children’s blood samples five days into the trials to look for any abnormalities and then change their treatment to the full-strength leading meningitis drug if there were any problems. However, they failed to do so. Instead, the Pfizer team waited for the irreversible symptoms to manifest physically before switching the treatment for the study’s unwitting participants. After realising that they had just murdered and crippled these children, Pfizer, like any giant pharmaceutical corporation would, left the scene of the crime in a hurry, failing to do any further evaluation of the patients.

Pfizer spent the next ten years denying any responsibility for the disaster, eventually releasing a statement entitled ‘Trovan, Kano State Civil Case—Statement of Defense’, in which the pharmaceutical bigwig stated among other things ‘that mortality in the patients treated by Pfizer was lower than that observed historically in African meningitis epidemics, and that no unusual side effects, unrelated to meningitis, were observed after 4 weeks’.

Pfizer eventually settled the case for $75 million on condition that it would not be held responsible for its actions. The Guardian newspaper reported in 2011 that the first four settlements in the lengthy court battle had been given to the families of four of the children who were killed during the trial. In an unabashed attempt to make the court settlement of $175,000 harder for each of the surviving families to claim, the victims’ families were forced to provide DNA samples to prove they were actually related to the deceased. This tactic turned out to be very effective from the company’s perspective, as many of the families didn’t trust Pfizer, which led some to pull out and refuse the settlement because they thought the DNA samples were a ploy by Pfizer to commit further illegal secret experiments upon them, or worse.

The Nigerians were represented by two brave lawyers, a Nigerian lawyer named Etigwe Uwo and a Connecticut-based lawyer, Richard Altschuler. According to Altschuler, it was the story of Pfizer’s Kano coverup that prompted John le Carré to write the novel The Constant Gardener that was adapted in the feature film. Like the situation depicted in the movie, Pfizer used scare tactics and smear campaigns to try and hinder any investigation into the Kano incident.

Læs “Folket misinformeres” hos Nordjyske S. Tidende

Link til anden vigtig artikel:

https://www.ft.dk/samling/20211/almdel/suv/bilag/122/2504915/

index.htm

Linket virker kun når hele linjen er med

https://www.ft.dk/samling/20211/almdel/suv/bilag/122/2504915/index.htm